Prolific author Louis

Salvator was an Archduke of Austria from the branch of the Hapsburg family which ruled

Tuscany when he was born in Florence, Italy in 1847. Still in his 20s he left the Imperial

service to devote himself to science and travel, and wrote 50 books - all but four about

the Mediterranean.

He lived in the Balearic island of Majorca

or on board his beloved steam yacht and produced, on average, a book a year. His work on

Nicosia was written when he was

26, and was based on a cruise to Cyprus. It was an inspiring city in 1873, five years

before British occupation.

He lived in the Balearic island of Majorca

or on board his beloved steam yacht and produced, on average, a book a year. His work on

Nicosia was written when he was

26, and was based on a cruise to Cyprus. It was an inspiring city in 1873, five years

before British occupation.

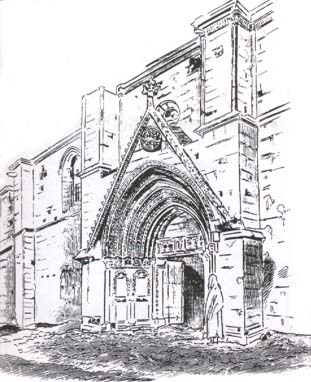

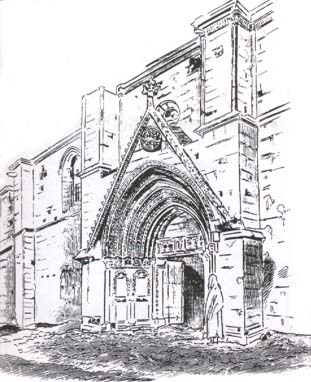

Salvator saw it through the eyes of an artistic young man,

and its romantic appeal enthralled him. His descriptions, and the delicate lined of his

own sketches, give the liveliest impression that remains of the life and customs of a

great city of the old Levant at the end of three centuries of Turkish rule.

The first German edition of the book, printed in 1873 in

Prague, is very rare and only three copies are known to have escaped destruction by fire.

Here is and extract:

"Nicosia is not divided into districts

in the usual sense of the word; the only divisions that could be drawn would be by the

different populations of the town. The Turks for instance, occupy the parts about the Gate

of Famagusta, near the mosque of Tahta Kale, and especially those between the Gates of

Kyrenia and Paphos. The Greeks have chosen principally the district between the

Episcopal

residence and Ayia Sophia for their dwelling-place, but are also sprinkled amongst the

Turkish population between the Gates of Kyrenia and Famagusta. The Armenians are mixed up

everywhere with the Turks.

"Nicosia is not divided into districts

in the usual sense of the word; the only divisions that could be drawn would be by the

different populations of the town. The Turks for instance, occupy the parts about the Gate

of Famagusta, near the mosque of Tahta Kale, and especially those between the Gates of

Kyrenia and Paphos. The Greeks have chosen principally the district between the

Episcopal

residence and Ayia Sophia for their dwelling-place, but are also sprinkled amongst the

Turkish population between the Gates of Kyrenia and Famagusta. The Armenians are mixed up

everywhere with the Turks.

"The narrow, winding streets bear sometimes various

names within a short distance, and usually the name of the street is not given, but the

various places are designated after the neighbourhood in which they are situated. The names

of the localities appear in white characters on blue tin tablets in Turkish and Greek. The

houses are numbered in the same manner. The pavement consists of rough shingle, and in

many cases there is none at all. The principle street of Nicosia, which is naturally the

broadest and the longest one, is called the next in importance to the Tahta Kale, which

leads from the Gate of Famagusta to the bazaars, thus forming the main entrance to the

city. By the side of it runs the dry bed of the Kanlidere /Pedias with several bridges.

"There are very few houses built of stone in Nicosia. Some of

these ate adorned with Gothic arched windows and flowing tracery, but nobody seems to pay

any attention to them. Most of the houses are made of big clay bricks, as they say, for

fear of earthquake. Clay houses will last a hundred years, but they must be frequently

repaired, as the straw in the bricks is plastered up and will rot and leave holes in the

wall.

"There are very few houses built of stone in Nicosia. Some of

these ate adorned with Gothic arched windows and flowing tracery, but nobody seems to pay

any attention to them. Most of the houses are made of big clay bricks, as they say, for

fear of earthquake. Clay houses will last a hundred years, but they must be frequently

repaired, as the straw in the bricks is plastered up and will rot and leave holes in the

wall.

"Most of the Turkish houses have prominent pavilions,

others latticework windows and are surmounted by wooden gables. Over the entrance of the

Turkish houses we often found a wooden frame in the shape of the crescent and star, or of

the star only, with little wire hoops to hold the oil cups for the illumination on the

anniversary of the Sultan's accession and other festivals.

"The entrance-doors usually exhibit three rows of

nails, one in the middle, one on the top, and one below; narrow strips of wood run down

closely from the top, each of them fastened by a nail in three places. Some of the doors

are formed in lozenge-shaped squares made in a similar manner. The cross-bars of the doors

are most elaborate in some Turkish houses.

"Now let us step in. The doors of the Turkish houses are in

most cases carefully locked, and a screen stands immediately behind, so that when the door

is opened no-one can see in. Having passed the screen, the visitor enters the paved hall,

usually facing a garden or a courtyard.

"Now let us step in. The doors of the Turkish houses are in

most cases carefully locked, and a screen stands immediately behind, so that when the door

is opened no-one can see in. Having passed the screen, the visitor enters the paved hall,

usually facing a garden or a courtyard.

"In the absence of arches, the roof is supported by

round columns, and the beam is then adorned with carved consoles. All the windows opening

into the hall are provided with Moorish lattice-work. From the entrance, the stairs lead

to the upper floor either by a regular staircase, or steps on the outside of the wall.

"Pretty little doors with carved Moorish arches form

the entrance to the interior. The floors and ceilings are inlaid with large,

dirty-grey

marble slabs, which come from the village of Eylence. The roof is generally

untiled; in

many cases it is pointed; for the most part, however, flat. Generally, the round beams are

ornamented by pretty basketwork, or else they are simply overlaid by boards. Rich people

have their floors inlaid. The doors are made of wood, often with fine fretwork.

"In the Turkish houses, we usually find a divan-room,

which is also frequently found in Greek houses. The ceilings of these rooms are usually

supported by arches resting on brackets, or simple beams. The floor is covered with mats

from Egypt, and in the middle of the room stands the copper fire-pan with glowing

charcoal. In the houses of the poorer, the rooms on the ground-floor are also inhabited,

and the light comes in through handsome-looking little windows made by apentures in the

thick stone walls, and having glass panes on the inside, like those usually found in the

mosques.

"The

Turkish inhabitants of the richer class have a reception room on the upper floor, richly

furnished with divans along the walls, and shelves garnished with various objects of glass

and china... This opens into other rooms with broad divans and pillows; sometimes in the

corners there are small shelves containing all sorts of bric a brac and slender

scent-bottles.

"The

Turkish inhabitants of the richer class have a reception room on the upper floor, richly

furnished with divans along the walls, and shelves garnished with various objects of glass

and china... This opens into other rooms with broad divans and pillows; sometimes in the

corners there are small shelves containing all sorts of bric a brac and slender

scent-bottles.

"Rich Turks have large latticed pavilions, which are

delightfully cool in summer if there is the slightest of breeze. They also act as a cool

resting-place, like the flat roofs of the houses. The kitchen is situated on the ground

floor, with the fireplace in the corner, or in the middle of the wall, after the Turkish

fashion. Many houses have a perfectly round baking-oven with a marble floor and stone

sides covered on the top with clay and straw. Most of the houses have their own wells;

otherwise the water is brought in by donkeys, which have two pitchers hanging on either

side.

"Almost every house has an orange garden, with

gigantic palms towering over the fruit trees; and besides these private enclosures there

are extensive public gardens within the boundaries of the city, occupying more than one

half of the whole extent of it. All these gardens are bounded by clay walls on the side of

the street; the side adjoining the open hall of the house is fenced only by a low wooden

balustrade; and they are watered either from cisterns or directly from the aqueducts. All

sorts of fruits are cultivated there, some are very sweet, orange-shaped lemons which are

very cheap on the island and can be bought therefore by the poorest classes, but citrons

of an extraordinary size, with very few stones, and a sort of white paste inside rot very

quickly, and are often preserved by putting a coat of wax over them.

"Almost every house has an orange garden, with

gigantic palms towering over the fruit trees; and besides these private enclosures there

are extensive public gardens within the boundaries of the city, occupying more than one

half of the whole extent of it. All these gardens are bounded by clay walls on the side of

the street; the side adjoining the open hall of the house is fenced only by a low wooden

balustrade; and they are watered either from cisterns or directly from the aqueducts. All

sorts of fruits are cultivated there, some are very sweet, orange-shaped lemons which are

very cheap on the island and can be bought therefore by the poorest classes, but citrons

of an extraordinary size, with very few stones, and a sort of white paste inside rot very

quickly, and are often preserved by putting a coat of wax over them.

"Apricots and other kinds of fruit are equally famous; St

John's bread, pomegranates and dates, which are rather dark-coloured, but very good. The

bunches of dates are wrapped up in soft straw mats to protect them from the millions of

ravens, rooks, and jackdaws, which sometimes cover the palm-trees in such numbers that

they appear quite black.

"Vines and mulberries are also frequent: these latter

are reared for the sake of the silkworms. The ground by the side of the fruit trees is

occupied by fine vegetable gardens, watered with the help of a sort of shovel, which takes

up the water like a spoon and throws it over a considerable area. Carrots, onions,

cabbage; these are eaten raw. Prickly pears and various flowers are plentiful."

References

References

Related Links

Related Links