| |

Between the Konak (or Atatürk Square)

in Nicosia and the Paphos Gate lies or lay one of the

capital's oldest quarters, now rapidly dissapearing before the housebreaker's ruthless

onsloughts. But when I first lived in Nicosia -a bare two hundred yards

away- this venerable enclave concealed behind high but tottering walls of mud brick some

dilapidated mansions of considerable age and a certain bygone dignity. Graceful arcades

that might collapse at any moment surrounded the inner courts of what once were mansions;

inside them, ceilings and galleries gaily carved and painted were crumbling slowly into

ruin. Narrow, tortous lanes twisted in and out of the quarter; here and there from its

sadly neglected gardens would rise secular cypress, noble and upright, its bronze green

tones suggesting, when seen against the turquoise sky, the colours on an old Persian tile.

Here was the family residence of Mehmed Kiamil Pasha, greatest Cypriote and most

distinguished Ottoman statesman of modern times.

|

|

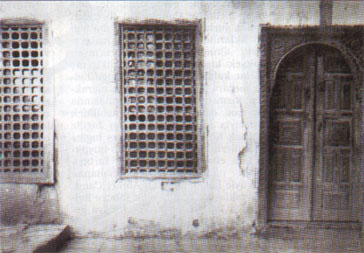

Entrance to Mehmed Kiamil Pasha's Paternal House,

Nicosia |

Kiamil Pasha's career was typical of typical of the Empire

he served so long and faithfully. His first post was in the household of the Pasha of

Egypt. In the course of his appointment he visited London for the Great Exhibition of 1851

in charge of one of the Pasha's sons and there began that daily reading of "The Times" which he told me in 1913, he had

never interrupted since then for a single issue. Kiamil's sojourn in England confirmed his

ripening admiration for this country and for its genius. Thenceforth, having full command

of English, he followed British affairs assiduously to the end of his life; thenceforth to

the close of his career he sought zealously the friendship of England for his country. He

cherished a deep affection for the British Royal Family, especially for King Edward VII

and Queen Alexandra, to whome he was warmly attached.

In Egypt, young Kiamil remained for ten years. Then, in 1860, he exchanged the service of

Abbas I for that of the Ottoman Government and for the ensuing nineteen years -that is to

say until he first entered the Turkish Cabinet- filled an astonishing number of

administrative appointments in every part of the empire. He governed, or helped to govern

many provinces, such as Eastern Rumelia, Herzegovina, Kosovo, and his native Cyprus whose

administration he lived to see removed from Turkish hands. He was not personally ambitious

although he rose rapidly; he was above all things a patriot and a scrupulously honest man,

the most ready of his countrymen to accept responsibility and undertake thankless tasks.

Four times between 1885 and 1913 he filled, and conferred rectitude and distinction upon,

the office of Grand Vizier, for the first time for centuries almost making a reality of

that sonorous phrase "Fuldiga Porta Ottomana" which

Neapolitan Foreign Ministers used to apply in their dispatches to the seat of the Turkish

Government. Then, in May 1913, the veteran octogenarian statesman unexpectedly appeares in

his native island, which he had not seen since he had ceased to govern it as far back as

1864.

The reason for the travels of the Grand Old Man of Turkey in the evening of his days was

no happy one. On the 23rd of the previous January, Enver Bey, as he was then, one of the

most forceful of the Young Turk leaders, burst with some of his associates into the

Sublime Porte while the Cabinet was actually in session, shot dead the Minister of War,

the genial and popular Nazim Pasha, at the Council table and overturned literally by force

Kiamil's fourth and last [Prime] Ministry. Unable to remain in Turkey after this bloody

coup, the ex-Grand Vizier was invited by his friend Lord Kitchener to stay with him in

Cairo, and after three months in Egypt decided to wait a favourable turn of fortune's

wheels, such as patience had brought him on previous occasions during the many

vicissitudes of his long and chequered career, in Cyprus. Suddenly conceived, then, as was

his journey and unforseen his arrival in the island, the provision of suitable

accomodation for someone of His Highness's (1) status presented a problem. As I was about

to go to Troodos for the summer, I offered him the loan of my house during my absence, a

suggestion the old gentleman was glad to accept.

Kiamil had landed in Cyprus with only two attendants, a valet and a black eunuch, but five

weeks later came the assassination of his Young Turk successor in the Grand

Vizierate,

Mahmud Shevket Pasha, possibly to avenge the murder of Nazim; and the prominent Old Turks

were either expelled or fled the country. Those included Kiamil Pasha's family, who had

hitherto been unmolested and now joined the old man in Nicosia. On my return from

Troodos,

Kiamil took the house next to mine, which was roomier and could accomodate his greatly

enlarged household. It was now a sight of considerable piquancy to watch from my window

his eldest son, Said Pasha, a decrepit roue and invalid of sixty or thereabouts, being

wheeled up and down the ramparts for his morning airing in a bathchair side by side with

the push-cart containing His Highness's youngest son, aged five or six. An unusual pair of

brothers.

|

|

|

Photograph showing Mehmed Kiamil Pasha seated |

On the 14th November following his arrival in the island, while full of plans for

revisiting England in 1914, Kiamil Pasha died suddenly of syncope while engaged in his

morning correspondence, and was buried that afternoon by his and my friend and landlord, Taib

Efendi, in the court of Arab Ahmed Mosque of

which Taib Efendi was the Imam. Truly Turkish in its contrasts and ups and downs had been

his life; truly Turkish was his burial. After a service in St.Sophia [Selimiye], the

great Mosque, the coffin was borne through the narrow streets of the walled town and

beneath overhanging lattices to its last resting-place, followed by the highest and lowest

in the island. Crowding upon the High Commissioner, the principal British officials and

the Moslem dignitaries, the rabble of the town struggled and pushed, instigated partly by

curiosity, partly by the hope of being able for a moment or two to take a part in the

bearing of the coffin.

As the procession approached the Arab Ahmed Mosque with its swaying burden a

flower-seller, dressed in the baggy white breeches of the Turkish peasant of Cyprus and

with bare legs and slippers, joined the throng, laid aside the tray of violets he had

brought into the bazaar for sale and put his shoulder under the coffin. It was the Grand

Vizier's nephew, his sister's son, who grew flowers and vegetables in the neighboring

village of Devtera and had come into the town that afternoon to ply his trade. He

encountered the procession accidentally, unaware of his uncle's death; but when he learned

who was being carried to burial, he took his place as a matter of course and no one

thought his participation strange.

For if the Ottoman Empire was an autocracy, it was in some respects the most striking of

democracies. It could give rank, honour and position to a man but not to his descendants;

a poor Turk or one of humble birth became Vizier or Mushir as easily as a Stambuli

Efendi.

The Turk needed not to be less gentleman because he wore peasant's clothes nor a parvenu

because he had reached eminence by a long ladder.

With his sense of fitness of things Sir Ronald Storrs, Governor of Cyprus from 1926 to

1932, caused a decent memorial to be raised over Kiamil Pasha's grave. He also composed

the English inscription, carved on the headstone below a Turkish one in old lettering. It

runs as follows:

|