|

|

The Monastery of St. Barnabas is at the opposite

side of the Salamis-Famagusta road, by the Royal Tombs. You can easily tell it by its two

fairly large domes. It was built to commemorate the foremost saint of Cyprus, whose life

was so intertwined with the spread of the Christian message in the years immediately

following the death of Christ.

Barnabas was a native of the ancient city Salamis, and was a Jew, though his family had

been settled for some time in Cyprus. His real name was in fact Joses, or Joseph; Barnabas

was the name given to him by the early Christian apostles because he was recognised as `a

son of Prophecy', or as Luke puts it `a son of consolation'. There is no contradiction

here. Luke is merely emphasising that one of the great historic functions of prophecy was

to console the believer and keep him in the faith.

He was reputed to be

an inspired teacher of Christianity, but more than that he played a very great role in the

development of early Christianity. He was also the man to acknowledge that Paul's

conversion to Christianity was absolutely sincere, and above all he recognised the genius

of Paul, whom he introduced to the Christian fellowship in Jerusalem. When Barnabas was

later sent to Antioch to supervise the work of the early Church there, he had Paul as his

assistant. Later still, of course, he undertook his great missionary journey with Paul,

visiting among other places, his own country of Cyprus.

Finally, of course, we know certainly that Paul and Barnabas had a strong diffrence

of opinion about Barnabas' nephew, John Mark, and the two friends parted company. Paul

wrote later that the rift was healed but by that time Barnabas was probably already back

in Cyprus.

The monastery which

bears Barnabas' name was originally built in the last part of the fifth century, to

commemorate the discovery of his body, and the dignity and the seniority it brought to the

early Christian Church of Cyprus. Parts of the early building have been preserved in the more recent churh which was built by

Archbishop Philotheos in 1756. The money for the purchase of the land on which the

monastery was built, is supposed to have been provided by the Byzantine Emperor at the

time Barnabas' body was found.

When you look carefully at the church you

will notice the traces of the original fifth century building and also places it seems to

have been enlarged and changed, probably in the very late mediaeval period. But in the

main it is fairly conventional Greek Orthodox architecture of the eighteen century.

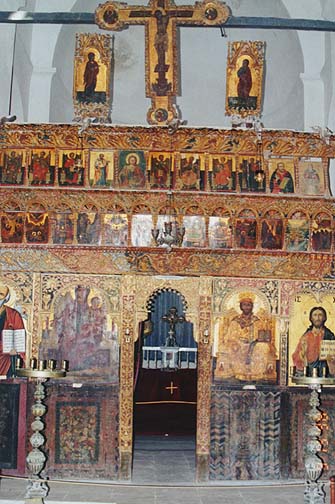

On one of the walls, the story of how Barnabas' body was shown to the Archbishop in

a dream, is rendered in small pictures. These were done in the present century, but some

of the icons and statues are a good deal older.

On another wall, somewhat incongruously,

hang wax replicas of limbs in a gesture of gratitude for the ailing limbs which the

Apostle Barnabas is supposed to have miraculously cured. Close by, the image of

st.

Heraklion stares at you from every angle you choose. All these items, ancient and modern

have been very well looked after and are shown with great oride by the curator of the

church.

On another wall, somewhat incongruously,

hang wax replicas of limbs in a gesture of gratitude for the ailing limbs which the

Apostle Barnabas is supposed to have miraculously cured. Close by, the image of

st.

Heraklion stares at you from every angle you choose. All these items, ancient and modern

have been very well looked after and are shown with great oride by the curator of the

church.

The marble columns supporting the domes are conspicuous and rather

spectacular. It is impossible to be certain, but these may well have come from Salamis. In one

sense, the little rock tomb in which Barnabas is supposed to have been found gives

the authentic flavour of the Christian evangelist and martyr much more effectively.

The church of St Barnabas is exactly as it was when its last three monks left it in

1976. The church apparatus ; pulpits, wooden lectern, and pews are still in place. It houses a

rich collection of painted and gilt icons mostly dating from the 18th century.

The carved blocks and capital blocks in the garden and cloister courtyard come from

Salamis. The black basalt grinding mill come from Enkomi.

The cloister

of the monastery have recently been restored and at present serve as the archaeological

museum. This section houses an exquisite collection of ancient pottery displayed

chronologically, representing the changes in morphology and decoration of pottery in

Cyprus from the Neolithic to the Roman times. The rest of the collection covers bronze and

marble art objects.

|